This book from Mark Manson was publicly available

https://img.codeanand.com/2025/07/29/SOLVED-Happiness-Guide.pdf

I passed it onto chatgpt, and ask it to explain each line of the Table of contents with a paragraph of takeaways and this is what it gave me

### Introduction

The introduction frames happiness not as a direct goal or switch to flip, but as a byproduct of living aligned with deeper principles—values, meaningful work, and connection. It warns against the modern “optimization” obsession and sets up the thesis: stop chasing happiness and instead unlearn faulty assumptions so that it can emerge naturally.

### The Origins of Human Happiness

Across traditions, happiness is understood as an effect of how one lives—virtue for the Greeks, right relationship and harmony in Confucianism, and alignment with deeper truths in spiritual systems—rather than a hedonistic pursuit. The “good life” emerges when life is structured around integrity, purpose, and connection, not when happiness itself is chased.

#### Hedonia: Happiness as Pleasure

Hedonia defines happiness as the experience of pleasure and absence of pain; early thinkers like Aristippus and Epicurus refined this, with Epicurus emphasizing tranquility (ataraxia) and moderation, warning against endless, vain desires. Lasting contentment, from this view, comes from simple, stable pleasures and avoidance of unnecessary wants rather than chasing intense highs.

#### Eudaimonia: Happiness as Flourishing and Virtue

Eudaimonia, per Aristotle, is flourishing through reasoned, virtuous activity over a whole life—not a transient feeling. It is cultivated through habit, requires practical wisdom, and judges a life’s happiness retrospectively based on character and contribution, making happiness an active process of becoming one’s best self.

#### Eudaimonia vs Hedonia: The Contemporary Revival

Modern psychology distinguishes hedonic well-being (short-term pleasure) from eudaimonic well-being (meaningful purpose), finding that pursuits tied to meaning and growth yield more sustained life satisfaction and health benefits—while pleasure is valuable, it’s fleeting and subject to diminishing returns.

#### Eastern Perspectives: Beyond the Self

Eastern traditions, especially Buddhism, reframe happiness as the removal of friction caused by attachment and resistance to reality; embracing impermanence and non-self leads to peace, making happiness less about achievement and more about releasing the causes of suffering.

#### The Confucian Way

Confucianism locates happiness in social harmony and right relationships—through appropriate action (li) and mutual responsibility—suggesting individual well-being is ecological, emerging from balanced, virtuous interplay within one’s relational web rather than isolated self-interest.

#### The Universal Pattern

Despite cultural differences, a common insight surfaces: happiness is not pursued directly but emerges when lives align with deeper principles—virtue, harmony, right action—across traditions, warning against the paradox of hedonism and privileging integrity over surface-level pleasure.

### The WEIRD Problem: When Happiness Research Goes West

Much of happiness research is based on WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) samples, which are outliers culturally and psychologically; generalizing their findings misrepresents global human experience, making the field blind to alternative conceptions of flourishing.

#### The Cultural Influence on Happiness

Culture shapes what happiness means—Western cultures valorize individual achievement and high-arousal positive states, whereas others (e.g., East Asian) prize balance, modesty, and harmony, so dominant metrics often reflect cultural bias rather than universal human needs.

#### The Measurement Problem

Standard global happiness metrics like the Cantril Ladder embed assumptions (individualistic ideal life, comfort with self-rating) that fail across cultures; they skew toward power/wealth and misinterpret self-reports, undermining cross-cultural comparability.

#### What Gets Lost in Translation

Well-being grounded in interdependence, communal identity, or cultural values (e.g., Ubuntu, Latin American “presente” and “simpatía”) is invisible to individual-centric scales; different societies have distinct “destinations” of flourishing, so meaningful comparison requires recognizing plural forms of happiness.

### The Three Components of Happiness

Happiness comprises affect (feelings), life satisfaction (cognitive evaluation), and meaning (sense of mattering); none alone suffices, but together they offer a more complete, albeit imperfect, portrait of well-being, underscoring that happiness is multidimensional.

#### Component 1: Affect (The Feeling Part)

Affect reflects moment-to-moment emotional tone and is complex—positive and negative emotions co-occur, and people have a “positivity offset”; yet it’s reactive to circumstances, making equating happiness solely with feeling good misleading.

#### Component 2: Life Satisfaction (The Thinking Part)

Life satisfaction is a reflective judgment of one’s life, relatively stable and sometimes diverging from affect; major life events show hedonic adaptation, meaning that external changes often have transient emotional effects but can still shift overall life evaluation depending on alignment with values.

#### Component 3: Meaning and Purpose (The Mattering Part)

Meaning provides enduring grounding—people in difficult circumstances can sustain high well-being if they feel their lives matter; it is separable from pleasure and satisfaction, and its absence can lead to anxiety and emptiness even when other components are positive.

### The Hedonic Adaptation Problem

Different happiness components adapt at different rates: affect changes quickly, life satisfaction more slowly and incompletely, and meaning hardly adapts—implying durable well-being arises less from chasing transient pleasures and more from pursuing meaningful goals and coherent life alignment.

### What Does — and Doesn’t — Make Us Happy

Sex shows up as a common candidate people assume will boost happiness, but like many pleasurable experiences it’s subject to adaptation and context. Quality, mutuality, and emotional connection matter far more than frequency or novelty; when it’s embedded in healthy relationships it contributes to well-being, but when used instrumentally or dysfunctionally its benefits are fleeting or even harmful. This nuance is signaled by its placement alongside other hedonic factors in the “What Does—and Doesn’t—Make Us Happy” section.

#### Money

Money buys comfort up to a point—covering basic needs and reducing stress—but beyond subsistence its direct effect on lasting happiness is limited because of hedonic adaptation. What matters more is how money is used: investing in experiences, reducing insecurity, and enabling autonomy and meaningful activity, rather than chasing ever-higher income as if that alone would yield durable satisfaction.

#### Fame and Status

Fame and status give social feedback that can temporarily lift self-esteem, but their contribution to happiness is tangled with relative comparison and the source of recognition; pursuing external admiration often leads to diminishing returns unless it’s aligned with competence, genuine respect, and internal values. The guide emphasizes clarifying what recognition truly matters and getting it in ways that avoid the pitfalls of chasing superficial prestige.

#### Physical Attractiveness

Being attractive correlates with higher reported well-being, largely because of indirect advantages like better social and economic treatment (“halo effects”), but much of that boost evaporates when those downstream benefits are controlled for; excessive pressure to look a certain way can even hurt. True self-respect through reasonable self-care—as opposed to seeking external validation—is framed as more sustainable for happiness.

#### Geography and Environment

Location and environmental features influence happiness mostly by shaping social and institutional contexts, not via superficial attributes like weather alone. Well-governed societies with safety, social support, and walkable, green neighborhoods foster higher well-being; adaptability means people often return to baseline unless environment aligns with their values or provides meaningful community.

#### Your Job/Career

Employment matters, but not all jobs equally: control, growth opportunities, supportive culture, and emotional regulation buffer against stress and are key drivers of job-related happiness. Unemployment or low-autonomy work depresses well-being, whereas meaningful, developmentally rich work and healthy work environments boost sustained satisfaction.

#### Love and Relationships

Close, high-quality relationships are central to long-term happiness; they provide security, meaning, and resilience in adversity. Marriage or partnership per se isn’t a guarantee—relationship quality is—yet longitudinal evidence shows those with enduring, supportive ties tend to be the happiest and healthiest later in life.

#### Friendships

Friendships function as a core social support system that bolsters happiness similarly to romantic love: they give belonging, buffer stress, and reinforce identity. Deep, trusted friendships contribute to long-term well-being more than broader but shallow social networks; investing in these ties pays dividends because they are less volatile and more meaningful.

#### Having Children

Children can provide profound meaning and purpose—one of the components that adapts least—but they also introduce stresses and changes that interact complexly with baseline and circumstantial happiness. The net effect depends heavily on expectations, support systems, relationship quality, and alignment with one’s values; meaning from parenting can sustain well-being even when day-to-day affect is challenging.

### The Experiencing vs. Remembering Self

Happiness is a tension between present-moment experience and the story you tell about your life afterward. The experiencing self reacts to immediate stimuli, while the remembering self weighs coherence, meaning, and narrative. True satisfaction arises when you align both: making daily choices that feel good now and will also be viewed as worthwhile in retrospect—requiring reflection and iterative course correction.

### Baseline Happiness: The 50% You Inherit

Roughly half of your happiness is set by genetic and stable disposition “set points”; identical twins raised apart show strikingly similar well-being, demonstrating the power of baseline. Knowing this reduces self-blame, tempers expectations, and invites strategic play—accepting what you can’t change while working skillfully within it.

### Circumstantial Happiness: The 10% That Surprises Everyone

Life circumstances—job, wealth, marital status—only account for about 10% of variance in happiness because of hedonic adaptation. While extreme negative conditions (poverty, chronic pain, isolation) do have lasting effects, most changes people chase yield diminishing returns; understanding this liberates one from postponing happiness and encourages focusing on what actually moves the needle.

### Intentional Happiness: The 40% You Control

This is the lever with the most traction: deliberate activities like nurturing relationships, contributing to causes (meaning), practicing gratitude, and choosing experiences over material consumption compound into lasting well-being. Happiness here isn’t pursued directly; it emerges when you invest in activities for their own sake—connection, growth, and purpose—forming a resilient “portfolio.”

### Your Happiness Portfolio

Think of well-being as an investment mix: baseline (stable “bonds”), circumstances (limited, slow-changing “real estate”), and intentional actions (high-leverage “stocks”). The smart strategy accepts the baseline, doesn’t overbet on circumstances, and regularly invests in intentional practices that compound—creating a balanced, durable system for happiness.

### Flow — Losing Yourself (in a Good Way)

Flow is deep absorption where challenge and skill align, often producing fulfillment that outlasts the momentary experience; it's less about feeling “happy” in real time and more about feeling alive and competent afterward. Regular flow states provide psychological nutrients like purpose and mastery, making them a reliable contributor to sustained well-being.

### Experiences vs. Stuff — Where Your Money Buys More Joy

Experiential purchases yield more enduring happiness than material ones because they improve in memory, support identity, resist comparison, and foster social connection, whereas material goods depreciate in satisfaction. The guide frames this as a subversive counterpoint to consumer culture: spend to create stories, not just accumulate things.

### Acts of Kindness — The Helper’s High

Prosocial behavior triggers reciprocal positive effects: doing good boosts your well-being (the “helper’s high”), enhances social acceptance, and creates virtuous cycles, but it must be balanced with self-kindness to avoid burnout. Intentional kindness builds meaning and emotion “out of thin air,” reinforcing that happiness often follows value-aligned action.

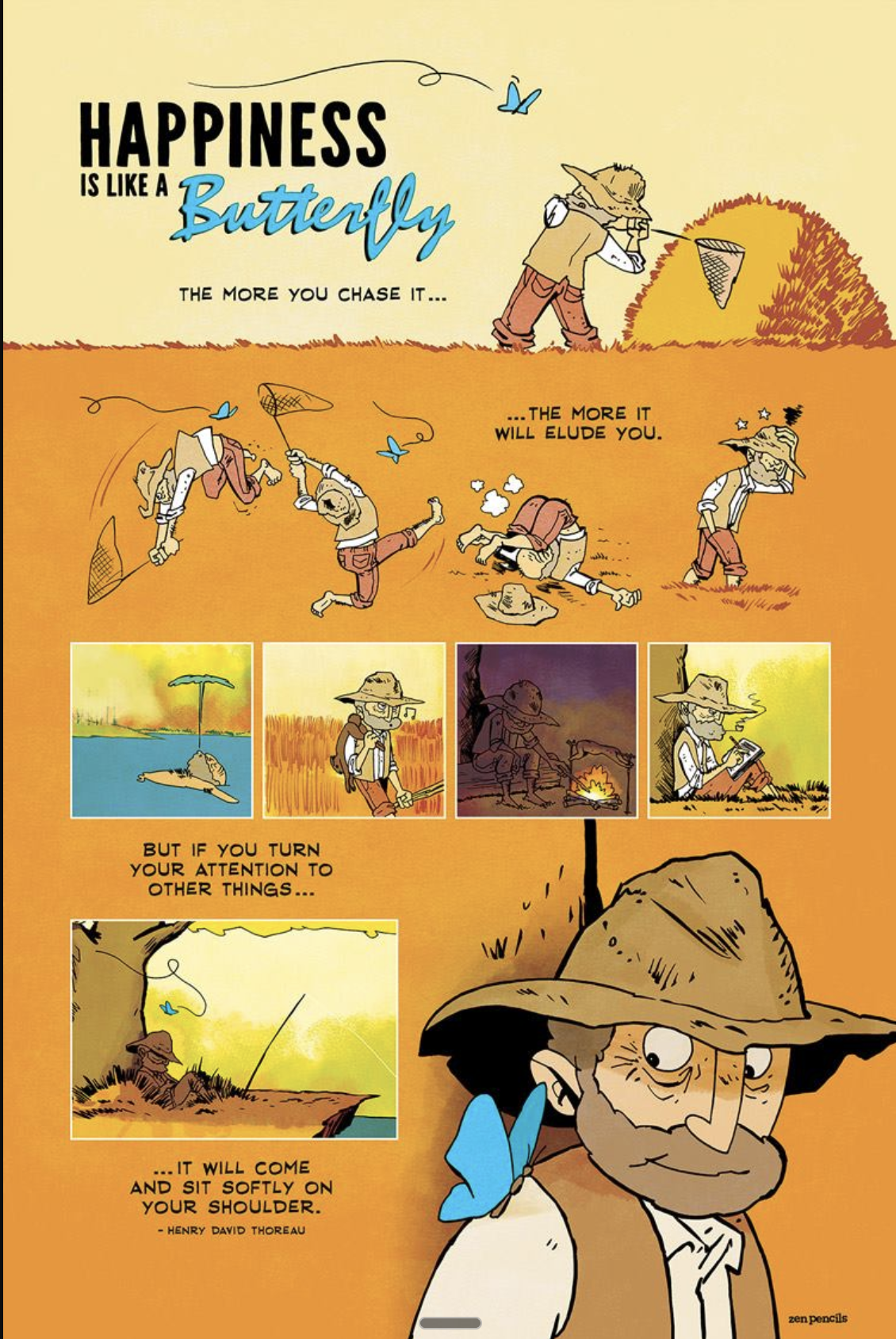

### The Paradox of Intentional Happiness

The most effective happiness-building activities aren’t about chasing happiness directly; they’re about growth, contribution, virtue, and connection. When pursued for their own sake, happiness naturally emerges as a byproduct—validating ancient wisdom that living well precedes feeling happy.

### Don’t Pursue Happiness; Remove Unhappiness

Actively chasing happiness can backfire; instead, remove impediments (stressors, toxic dynamics) and focus on foundational health. The “Backwards Law” reframes the goal: accept life's discomforts while eliminating unnecessary blockers, and happiness emerges as the consequence of a well-aligned life rather than a forced objective.

### Comparison is the Thief of Joy

Constant social comparison warps perception of progress and satisfaction: it makes you measure yourself against external, often misleading benchmarks instead of engaging with your own trajectory, creating unnecessary misery even when circumstances aren’t objectively bad.

#### The Direction of Comparison Matters

Who you compare yourself to changes the effect: upward comparison can sting but spur growth if the gap feels achievable, whereas downward comparison gives temporary relief but risks complacency and stalls improvement.

#### Similarity Drives Comparison

We naturally compare ourselves to people “like us” because those comparisons feel informative and manageable; the sweet spot is slightly better peers who challenge without demoralizing, which makes social benchmarking both motivating and psychologically safer.

#### The Local Dominance Effect

Local, proximal comparisons (e.g., friends, coworkers) carry far more emotional weight than distant or aggregate benchmarks; feeling “big” in a small pond or inadequate in a high-performing circle illustrates that nearby peers shape self-evaluation disproportionately.

#### Why Local Comparisons Hit So Hard

Because we interact with and get feedback from those closest to us constantly, their status and performance feel real and salient, inflating or deflating our self-view independent of broader context—making it critical to choose meaningful internal benchmarks instead.

### The Paradox of Choice

More options can reduce happiness: abundant choice increases paralysis, rising expectations, opportunity costs, and self-blame, so having “more” doesn’t mean better satisfaction—often the opposite.

#### The Psychology of Too Many Options

Cognitive overload from excessive options leads to decision avoidance, degraded satisfaction, and regret; experiments (e.g., jam selection) show that more choices can hinder action and reduce happiness rather than enhance it.

#### Two Approaches to Decision Making

People tend toward maximizing (seeking the absolute best) or satisficing (settling for “good enough”), and understanding which style you default to clarifies why some decisions exhaust you while others leave you content.

#### Maximizers: The Perfectionists

Maximizers exhaust themselves chasing optimal choices, leading to higher regret, lower life satisfaction, and greater susceptibility to upward comparison—even if their choices may be objectively better, the psychological cost undercuts happiness.

#### Satisficers: The Pragmatists

Satisficers set criteria, choose the first option that meets them, and move on; this reduces second-guessing, stress, and regret, yielding higher contentment and resilience in abundant-choice environments.

#### From a Maximiser to a Satisficer

You can retrain yourself: prioritize high-leverage decisions, predefine “good enough” criteria, limit options and research time, and commit—shifting focus from perfection to effectiveness increases happiness by reducing overanalysis.

### How Happiness Changes Across Your Lifetime

Happiness follows a robust U-shaped curve: emotional turbulence in youth, a midlife dip that is normal (not failure), and a rebound in later years, reflecting evolving priorities, regulation, and perspective—so the trajectory is typical, not pathological.

#### The Surprising Shape of Lifelong Happiness

The midlife slump and later-life comeback are consistent across cultures and socioeconomic groups; understanding this pattern reduces self-blame during dips and instills hope for the future by framing it as part of normal human development.

#### The Intensity Years: Your 20s and 30s

Emotional volatility in early adulthood is expected and valuable; using that intensity to document peak experiences while building regulation skills (e.g., through meditation or therapy) lays a foundation for stable long-term well-being.

#### The Middle Age Squeeze: Your 40s and 50s

The midlife dip is not a sign of failure but a common phase; resilience comes from small, meaningful adjustments—investing in relationships and emotional skills rather than chasing dramatic fixes.

#### The Happiness Comeback: Your 60s and Beyond

Later life tends to bring rising happiness due to improved emotional regulation, wiser goal selection, and deeper focus on what matters; narrowing priorities reflects accrued wisdom rather than resignation.

#### What Changes: The Components of Later-Life Happiness

Older adults get better at choosing goals strategically and regulating emotion, so even as some capacities decline, overall well-being can improve through wise reasoning and selective investment in meaningful domains.

#### What This Means for Your Life Right Now

Knowing these life-stage patterns lets you interpret your current feelings without self-blame: use youth’s intensity wisely, normalize midlife shifts, and recognize later-life gains as real—focus on sustainable practices over reactive fixes.

### The Myths of Happiness

Common narratives about happiness (constant positive feeling, total control, others having it easier, expiration with age, future arrival) are traps that misframe happiness as something to be obtained instead of engaged with; debunking them reveals more actionable, realistic paths.

#### Myth #1: “Happiness Means Feeling Good All the Time”

Expecting constant positivity backfires; emotional diversity is healthy and adaptive, and believing you should feel good nonstop amplifies distress when negative emotions inevitably appear.

#### Myth #2: “You Should Be Able to Control What You Think and Feel All the Time”

Total control is an illusion; trying to suppress or manufacture emotions often worsens them, whereas acceptance and working with feelings (emotional aikido) gives real influence without the burden of impossible standards.

#### Myth #3: “Others Have It Easier”

Comparing your messy behind-the-scenes with others’ polished highlights fosters loneliness and distorted perception; recognizing misperception and the corrosive effect of comparison helps recalibrate toward your authentic context.

#### Myth #4: “It's Too Late to Be Happy”

Believing happiness has an expiration date misinterprets aging; growth, meaning, and change remain possible throughout life, and reframing aging shifts it from decline to continual evolution and opportunity.

#### Myth #5: “I'll Be Happy When X Happens”

The arrival fallacy leads to perpetual postponement; tying happiness to future milestones sacrifices present joy, whereas aligning goals with values and appreciating the journey uncovers happiness in the now.

### Beyond the Myths

The common flaw of these myths is treating happiness as a solvable problem instead of a lived practice; the antidote is engagement with life’s complexity—accepting limitations, relinquishing false control, and building habits that support well-being.

### The 80/20 Guide to Happiness

The guide encourages focusing on the few high-leverage actions (the “20%”) that move the needle on well-being and building systems to sustain them, rather than accumulating more steps or chasing low-impact changes.

### Further Reading

This section points to the underlying research and expanded sources, inviting deeper exploration and supporting the guide’s claims, reinforcing that the conclusions are grounded in a diverse, evidence-based literature.

-----

Relates a lot to [[Literature notes/The Courage to be disliked|The Courage to be disliked]] and